Philosophy, humanities

Arturo Tozzi

Former Center for Nonlinear Science, Department of Physics, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas, USA

Former Computationally Intelligent Systems and Signals, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

ASL Napoli 1 Centro, Distretto 27, Naples, Italy

For years, I have published across diverse academic journals and disciplines, including mathematics, physics, biology, neuroscience, medicine, philosophy, literature. Now, having no further need to expand my scientific output or advance my academic standing, I have chosen to shift my approach. Instead of writing full-length articles for peer review, I now focus on recording and sharing original ideas, i.e., conceptual insights and hypotheses that I hope might inspire experimental work by researchers more capable than myself. I refer to these short pieces as nugae, a Latin word meaning “trifles”, “nuts” or “playful thoughts”. I invite you to use these ideas as you wish, in any way you find helpful. I ask only that you kindly cite my writings, which are accompanied by a DOI for proper referencing.

THE HIDDEN DIMENSIONS OF REALITY

Most of us grow up thinking the world is made of things: atoms, cells, organisms, planets, brains, tables, cats. But there is another way to think about reality, one that scientists increasingly use when simple objects no longer explain what we see. Instead of imagining the world as a collection of separate items, we can think of it as a collection of descriptions. A description is simply the way something appears when seen from a particular point of view. A rock has a shape, a movement has a trajectory, a heartbeat has a rhythm, and a thought has a structure of its own. Everything we know comes to us this way: not as raw matter, but as patterns that we interpret.

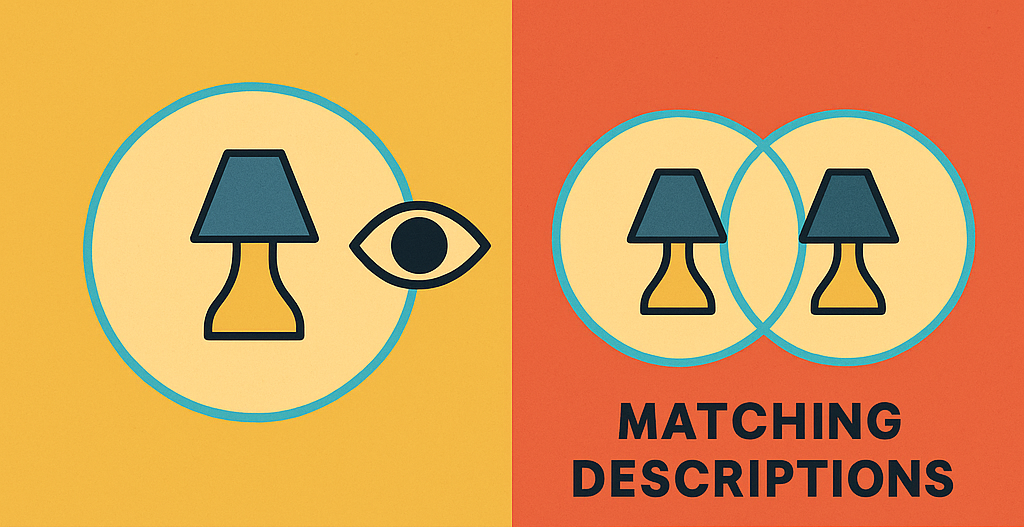

What is surprising is that the same thing can look completely different depending on the “dimension” of the description we use. A description with few dimensions may show us only the most obvious aspects, while a description with more dimensions may reveal relationships and hidden structures we never suspected. Imagine placing a lamp behind a glass sphere. If you look straight into the sphere, the lamp may appear twice. The world has not changed; your mode of description has. The sphere adds a kind of extra dimension to your viewpoint, splitting one appearance into two perfectly coordinated images. These two images are what the theory calls matching descriptions. They are two expressions of a single underlying reality, made visible because we have shifted to a richer level of observation.

This idea generalizes far beyond optical tricks. Nature hides many of its symmetries (repeating structures, invariances, regularities) until we change the scale or the dimensional setting from which we look. A chaotic system may look random when viewed in ordinary space but reveal a clean, repeating pattern when represented in a higher-dimensional phase space. Two biological structures that seem unrelated, i.e., the branching of a lung and the branching of a plant root, may turn out to follow the same deep geometric logic. Even the way our brains recognize shapes, predict movements, or recall memories involves detecting these hidden correspondences. Matching descriptions, wherever they appear, show that what seemed separate may be two faces of the same structural pattern.

Many processes in the world also repeat in loops: breathing, heartbeats, sleep cycles, ecological rhythms, even habits of thought. In this framework such loops are called strings, i.e., paths that return to where they began. Strings are simply recurring patterns, and when we study them from a higher-dimensional angle, we often find matching descriptions hidden along their cycles. These are the symmetries that give the loop its stability and coherence.

To organize all the ways descriptions can vary, the theory introduces an abstract concept called the Monster. This name might sound dramatic, but here it simply refers to the total space of all possible descriptions, including those our universe never uses. Think of it as the ultimate map of all potential structures. Our physical universe occupies only a small region of this map. There may be many other regions filled with patterns we never encounter, yet this wider framework helps us understand what kinds of structures are possible and how the structures we observe relate to this larger landscape. Scientists regularly use similar ideas in physics and mathematics — configuration spaces, state spaces, manifolds, but the Monster is the largest such space we can imagine.

This perspective becomes especially powerful when we apply it to the brain. The brain does not simply record the world; it actively transforms simple descriptions into richer ones. When your eyes detect a cat, the initial signal is extremely limited: just light on the retina. But your brain quickly elevates this into a higher-dimensional pattern that includes recognition, memory, prediction, emotional tone, and conceptual structure. In this sense, your brain constantly turns single descriptions into matching descriptions, revealing correspondences that were not present at the sensory level. The “mental cat” is not a weaker version of the real cat. It is a structurally richer representation because it lives in a space with more dimensions, dimensions created by the brain itself. Attention acts as a spotlight deciding which descriptions should be expanded in this way, and time provides the sequence along which these expansions unfold.

Seen from this angle, the world is not primarily a collection of objects but a network of patterns that transform as we shift descriptive levels. What looks disconnected can become unified when viewed from the right dimension. What looks random may hide a structure that only appears when our viewpoint widens. What seems unique may turn out to have a counterpart we had never noticed.

The deeper message is simple: understanding any system (a physical process, a living organism, a thought) requires finding the level at which its hidden symmetries and matching descriptions become visible. At that level things that once seemed mysterious or unrelated suddenly make sense. If they still look unrelated, we may simply be looking from the wrong dimension. The world is full of structures waiting to be revealed. Many of them are not hidden at all; they are merely positioned one dimension above where we are currently looking.

NUGAE - A MAP OF EPISTEMIC STRATEGIES AT THE OUTERMOST LIMITS OF LANGUAGE

Language functions as the primary medium of scientific and philosophical inquiry, but it is also finite. Yet there are moments when the inherited grammar (mathematical, logical or natural) ceases to hold. Equations diverge into singularities, models collapse into undecidability and words themselves dissolve into paradoxes. These limit-situations are not merely technical obstacles but epistemological thresholds, revealing that language is a finite instrument that delimits knowledge.

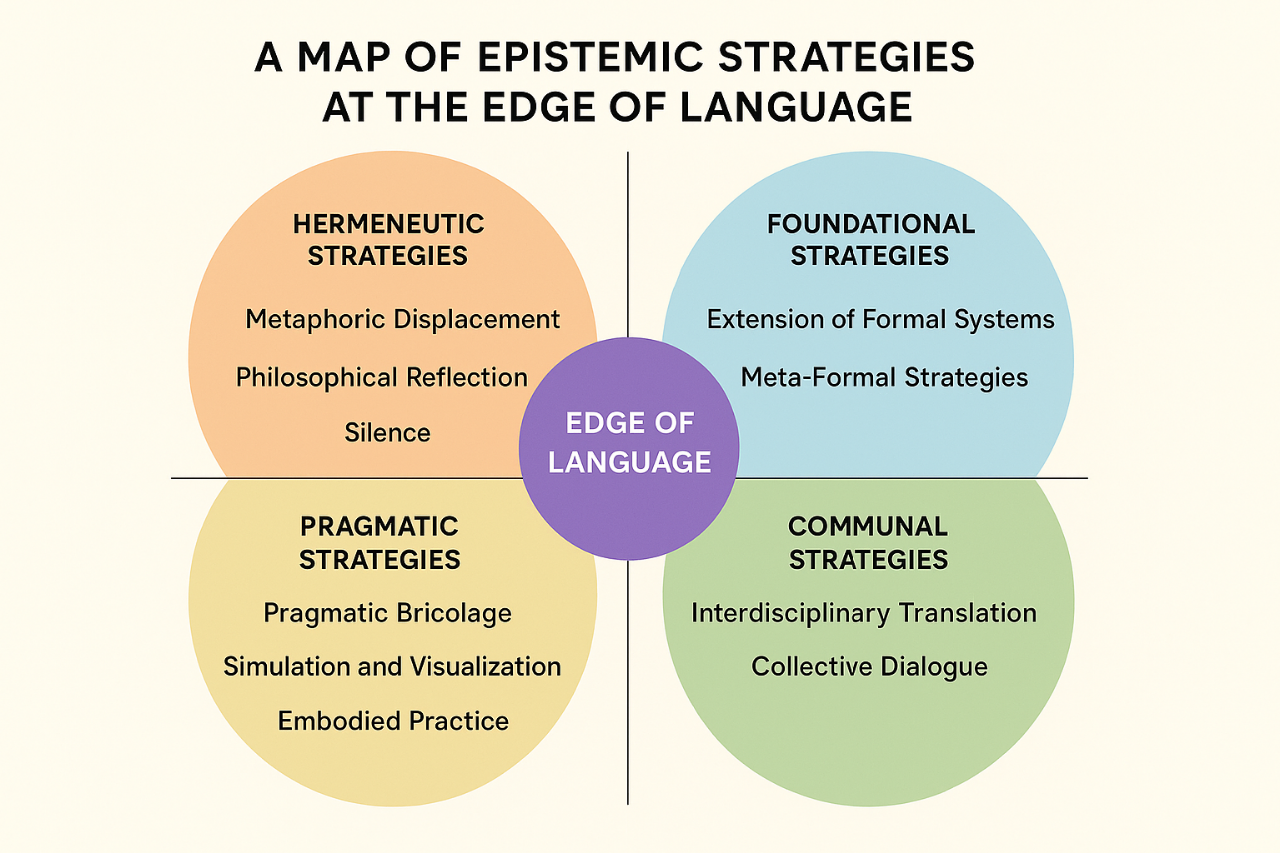

To engage with these thresholds, a variety of epistemic strategies have been developed. The following systematization arranges strategies into conceptual families, offering a provisional cartography of how inquiry navigates the edge of language to cope with “singularities”, i.e., breakdown points where established forms of description collapse or diverge.

1. Foundational strategies: extending and reinventing formalism

1.1 Extension of formal systems. When established frameworks reach breakdown points, new symbolic systems to expand the formal apparatus are created to absorb anomalies. Historical examples include the invention of complex numbers to handle square roots of negatives, non-Euclidean geometries to transcend Euclid’s fifth postulate or Hilbert spaces in quantum mechanics. The singularity is thus recast not as an endpoint, but as a generative site for mathematical innovation.

1.2 Meta-formal strategies. Instead of inventing entirely new systems, existing logics may be generalized. For instance, paraconsistent logics allow contradiction without collapse, fuzzy logics accommodate gradations of truth and category theory reorganizes structures at a higher level of abstraction. These strategies domesticate limit-cases, offering rigor where classical formalism fails.

2. Pragmatic strategies: working with what is at hand

2.1 Pragmatic bricolage. Scientists often employ ad hoc mixtures of symbols, diagrams, natural language and computer code to move forward. These hybrid forms lack systematic unity but enable progress by leveraging multiple representational resources. Bricolage emphasizes functionality, reflecting the practical dimension of inquiry at the edge.

2.2 Simulation and visualization. When verbal or mathematical language falters, visual and computational models step in. Simulations can “show” dynamic processes and systems that resist concise description, while visualizations transform complexity into perceptual patterns. These strategies rely less on propositions and more on experience through representation.

2.3 Embodied practice. Language is supplemented by embodied action: experiments, prototypes and manipulations of matter. Tacit knowledge, gestures and practices express what words cannot fully capture. Embodied practice emphasizes that knowing is not only linguistic, but also corporeal and situated.

3. Communal strategies: beyond the individual voice

3.1 Interdisciplinary translation. Borrowing vocabularies from other disciplines provides new expressive tools. For instance, physics adopts topological language from mathematics; biology draws from information theory and computation. Translation generates hybrid idioms that extend beyond the limits of a single disciplinary language.

3.2 Collective dialogue. Some boundaries can only be softened through the interplay of perspectives. Dialogues, debates and communities of practice co-create new idioms that no single mind could devise. Language here evolves socially, highlighting the collective dimension of epistemic creativity.

4. Hermeneutic strategies: making sense with meaning beyond calculation

4.1 Metaphoric displacement. Where formalism collapses, metaphor provides provisional scaffolding. Scientific metaphors such as “black hole,” “genetic code,” or “molecular lock and key” function as bridges, rendering the incomprehensible graspable through analogy. Metaphor is not literal truth but a vehicle for navigating the gap between language and phenomena.

4.2 Philosophical reflection. Philosophy interrogates the conditions of language itself, asking whether the breakdown is ontological (in the world) or epistemic (in our categories). This strategy shifts the focus from objects to the structures of thought, examining the limits of representation and the meaning of “unsayability.” It re-situates singularities as questions about the relationship between language, thought and being.

4.3 Silence. Silence acknowledges the unsayable without forcing premature articulation. Wittgenstein’s dictum “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”captures this stance. Silence is not a void but a disciplined pause, leaving open the possibility of future languages.

Overall, our taxonomy suggests that the edge of language is not a terminal boundary but a generative field. No single approach can overcome this limit in isolation; yet, taken together, these strategies constitute a plural epistemic repertoire. Such a repertoire may open new avenues for addressing radical limit-situations of thought, including Being, consciousness and qualia.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 20205. Nugae -a map of epistemic strategies at the outermost limits of language. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.17515.40481

NUGAE - TRUTH AND SENSE AS A UNIFIED CATEGORY: COLLAPSING FALSE AND MEANINGLESS INTO TRUTHLESS

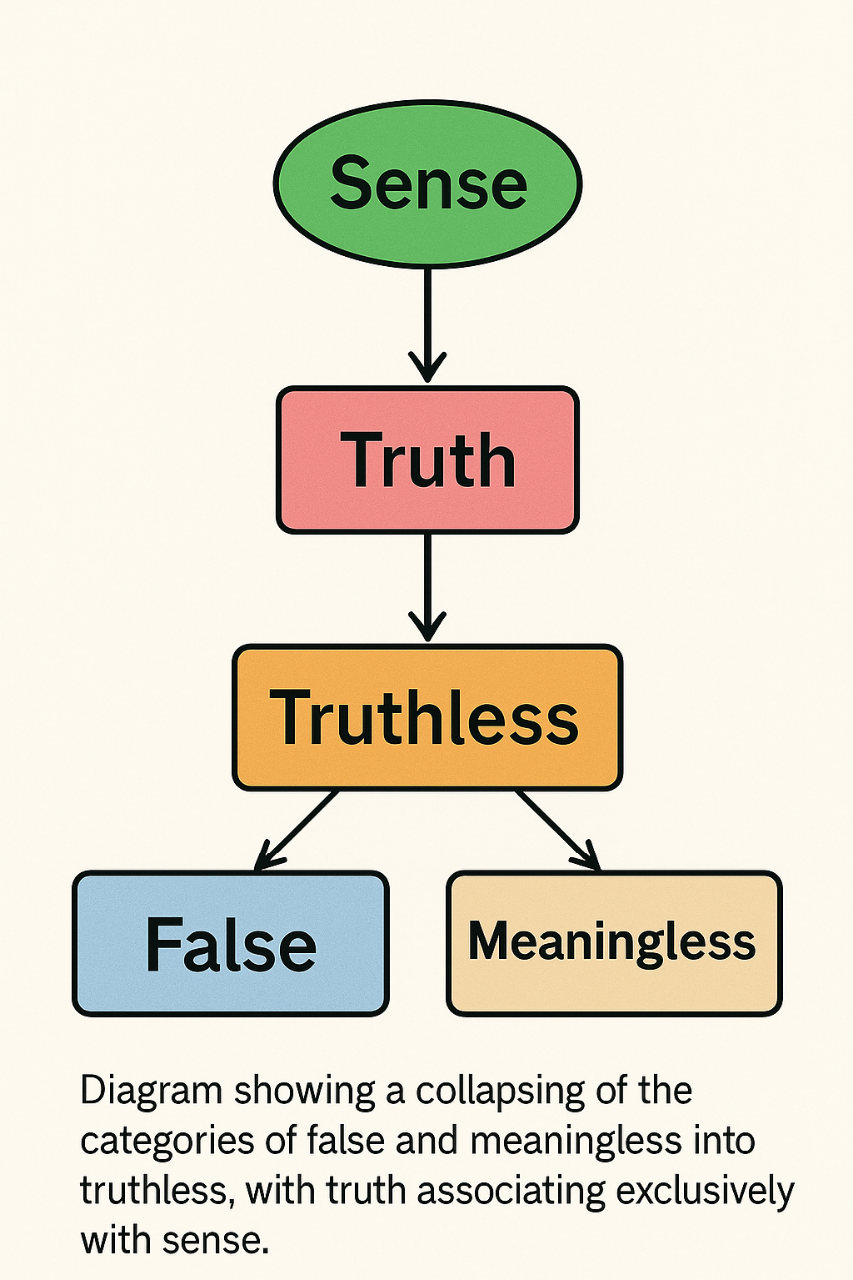

In contemporary philosophy of language and logic, there is a long-standing separation between what is false and what is meaningless. Classical semantics, following Frege and early Wittgenstein, allows for three categories: statements that are TRUE, statements that are FALSE and statements that are SENSELESS because they fail to properly refer or to form a coherent proposition. This threefold scheme allows the distinction among different failures in discourse, yet it also multiplies categories and forces scientists and philosophers to wrestle with the distinction between something that is false and something that simply does not make sense. In practice, both end up excluded from the realm of truth, but the analytic gap remains.

We propose to collapse this threefold distinction by defining senselessness as nothing other than truthlessness. Any statement that cannot be true, whether because it is factually incorrect or because it is semantically malformed, belongs to the same class. Truth becomes the only positive category, applying strictly to propositions that are both sense-bearing and empirically valid, while everything else is classified as truthless. This redefinition reduces the semantic landscape to two poles: truth and truthlessness. A statement like “the lac operon is upregulated by lactose” is true; “the lac operon is upregulated by glucose” and “the lac operon is upregulated by triangles” are both truthless. One is false within biology, the other is nonsense, but they occupy the same category of non-truth.

The advantages of our twofold approach are several. First, it simplifies the logical scheme, reducing ambiguity and the temptation to treat nonsense as if it had a privileged status. Second, it aligns scientific practice with epistemic hygiene: whether a claim fails by contradiction with data or by conceptual incoherence, its status is the same, namely, truthless. Third, it removes loopholes often exploited in pseudoscience or mysticism, where senseless formulations are smuggled in as though they could point to hidden truths.

Experimental tests of this framework can be pursued in linguistic corpora and scientific discourse. One could classify statements from biology, physics or medicine according to whether they bear sense and whether they correspond to empirical evidence. Once senselessness is redefined as truthlessness, error rates in categorization are predicted to decrease and logical modeling of discourse becomes more efficient. In biology, Boolean or network models of gene regulation could be streamlined by mapping false and undefined states into a single truthless state, simplifying simulations and reducing computational overhead.

Beyond logical economy, this unification could recalibrate how we evaluate statements in science, philosophy and even machine learning. In artificial intelligence, it would discourage models from producing “plausible nonsense”, since senseless output is automatically labeled truthless. In education, it would highlight that truth is the primary positive category, while all other claims, whether false or meaningless, belong to a single, undifferentiated class. In research, it could inspire new semantic filters for scientific publishing, automatically discarding truthless claims whether they are false or incoherent.

Future avenues may include formalizing our system into new logical calculi, designing algorithms that operationalize truthless detection and exploring its implications for epistemology, where the boundary between sense and truth becomes a single threshold rather than two.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 2025. Nugae -truth and sense as a unified category: collapsing false and meaningless into truthless. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.18147.82726

NUGAE - NATURE’S UNIFORMITY: RECONCILING SCIENTIFIC REALISM AND CONSTRUCTIVISM

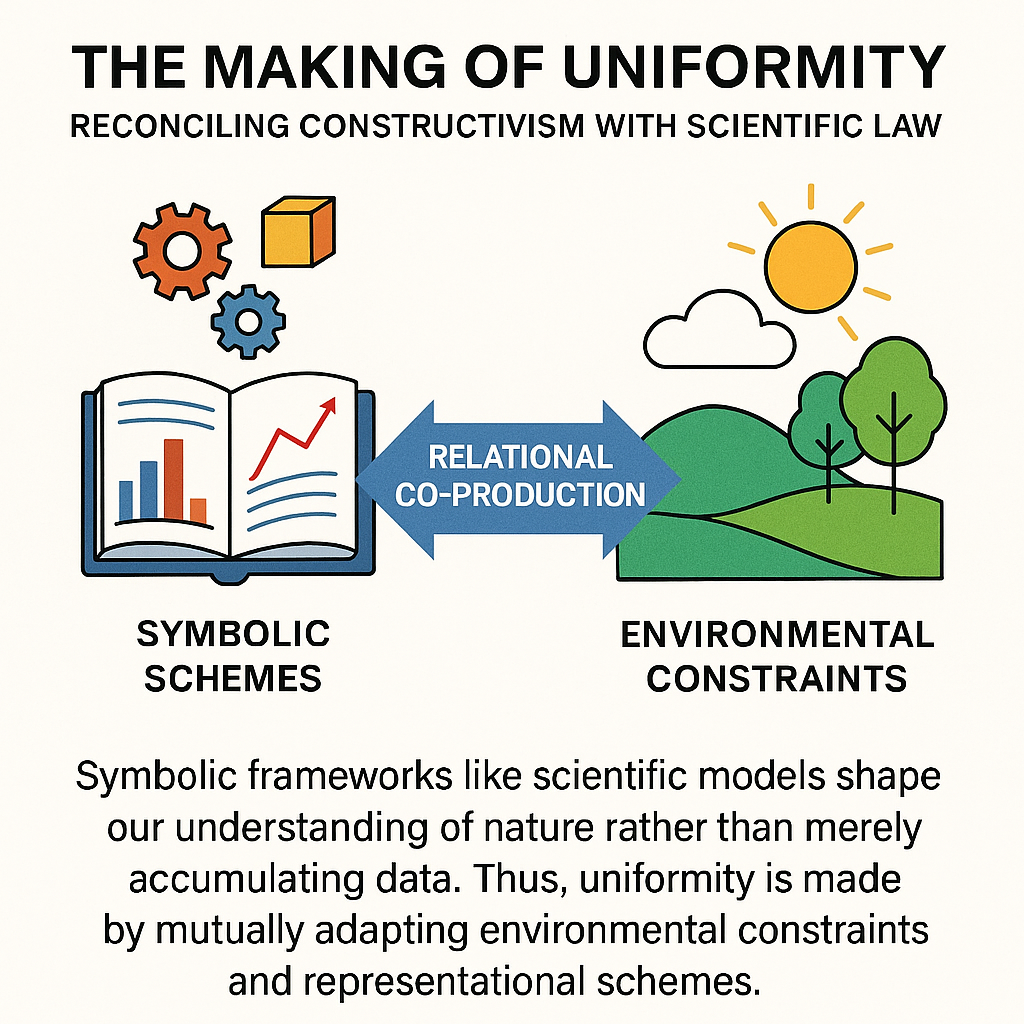

The assumption of uniformity of nature has served as a cornerstone in philosophy of science for explanatory and predictive practices. Classical empiricism has treated this uniformity as either a brute fact or an indispensable postulate without which induction and scientific reasoning would collapse. The various forms of scientific realism have assumed that nature possesses intrinsic order, laws describe preexisting regularities and successful prediction confirms our access to these uniformities. Against this backdrop, Nelson Goodman’s constructivist claim that “the uniformity of nature we marvel at belongs to a world of our own making” undermines realist accounts. If uniformity is not given in nature but arises from our symbol systems and classificatory practices, then the laws of science cannot be straightforwardly interpreted as mirrors of reality. This raises the question of how to reconcile the undeniable success of science with the intriguing thesis that uniformity of nature is not inherent but constructed.

We propose that uniformity of nature should be understood as an emergent relational feature arising from the interaction between symbolic schemes and the recurrent patterns of experience. It results from the fit between worldmaking practices and environmental constraints, a fit that science continually refines through experimental feedback. Therefore, scientific laws function as instruments rather than mirrors: they stabilize our engagement with phenomena by organizing patterns of recurrence in ways shaped both by environmental structures and by human symbolic activity. Regularities are neither simply discovered nor invented, but co-produced. They become visible only when cognitive and symbolic frameworks are applied to the flux of phenomena, generating intelligible structures to test, revise and extend.

To provide an example, think about weather forecasts: scientists use models refined to fit reality (like maps of air pressure or wind) to match repeating patterns in the atmosphere.

Our proposal of uniformity of nature as a relational co-production between symbolic schemes and environmental constraints draws inspiration also from Dewey’s pragmatism, Putnam’s pluralism, van Fraassen’s constructive empiricism and contemporary cognitive science, particularly Andy Clark’s predictive processing and Richard Menary’s cognitive integration. However, unlike these accounts, our aim is not to elaborate further philosophical insight, but rather to pragmatically suggest ways to generate testable predictions and outline directions for future research.

Our framework can be experimentally tested by analysing the performance of competing scientific models under conditions of novelty and stress. If uniformity were intrinsic, models should converge on the same structures regardless of symbolic framing. If it were arbitrary, success should be evenly distributed across frameworks. In turn, our relational thesis predicts instead that models closer to the constraints of phenomena will outperform others in predictive and technological success, but only relative to the symbolic categories available at the time.

Testable hypotheses include that shifts in symbolic frameworks (for instance, from Newtonian to relativistic physics) alter what counts as uniformity without invalidating the pragmatic fit of earlier models in their proper domains. Further examples can be found in the transition from classical genetics to molecular biology, where, e.g., the symbolic shift from “hereditary factors” to “genes as sequences” redefined what counted as uniformity in inheritance, yet left Mendelian ratios

Predictive success will not rest on a single uniformity, but on the relational adequacy of the chosen symbolic scheme to the particular experimental condition. For instance, quantum field theory and string theory impose different symbolic categories and their relative success should be judged by the fit between the representational tools employed and the constraints revealed by high-energy experiments.

In epistemology, our theoretical perspective may provide a middle-grounded way to reframe debates about realism and constructivism, showing how scientific laws can be treated neither as mere inventions nor as mirrors of nature, but as relational achievements arising through interaction.

In cognitive science, it supports accounts of perception and reasoning as constructive processes tuned to environmental stability, echoing predictive processing theories (from Kant to Friston) in which brains impose generative models on sensory input, with success depending on how well those models capture recurrent constraints.

In artificial intelligence, our view suggests that machine learning systems may not uncover inherent laws, but create mappings between input structures and environmental constraints. For example, in reinforcement learning, algorithms may succeed not by revealing hidden uniformities but by refining symbolic schemes to exploit stable patterns within data environments.

The same applies to natural language processing, where statistical models may not extract fixed linguistic laws but build relational fits between symbolic categories and communicative practices.

In medicine, predictive models of disease spread or treatment response may succeed insofar as they align symbolic constructs like “risk factors” or “biomarkers” with actual environmental and biological constraints.

Future research may further formalize this view using tools from information theory to measure mutual information between symbolic frameworks and phenomena, or from network science to evaluate the structural alignment between representational models and empirical systems.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 2025. Nugae -nature's uniformity: reconciling scientific realism and constructivism. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.21544.23041

NUGAE - BEING AND LIFE: A MATHEMATICAL FRAMEWORK FOR BIOLOGICAL EXISTENCE

The question of being has accompanied philosophy since its inception, from Parmenides’ assertion that “being is” and “non-being is not,” through Aristotle’s ontology of substance, to Heidegger’s attempt to retrieve the forgotten difference between being and entities. Traditionally, philosophy has treated being as the most universal and indeterminate concept, irreducible to any particular. Within metaphysics, God, the Idea of the Good or the Absolute have often been interpreted as the supreme expression of being. Yet this trajectory has remained largely detached from the empirical sciences, where the focus lies not on being in general but on specific entities and processes like molecules, cells organisms and ecosystems, all of which are concrete manifestations of life. A rigorous definition of “biological being” has not been formalized in mathematical terms.

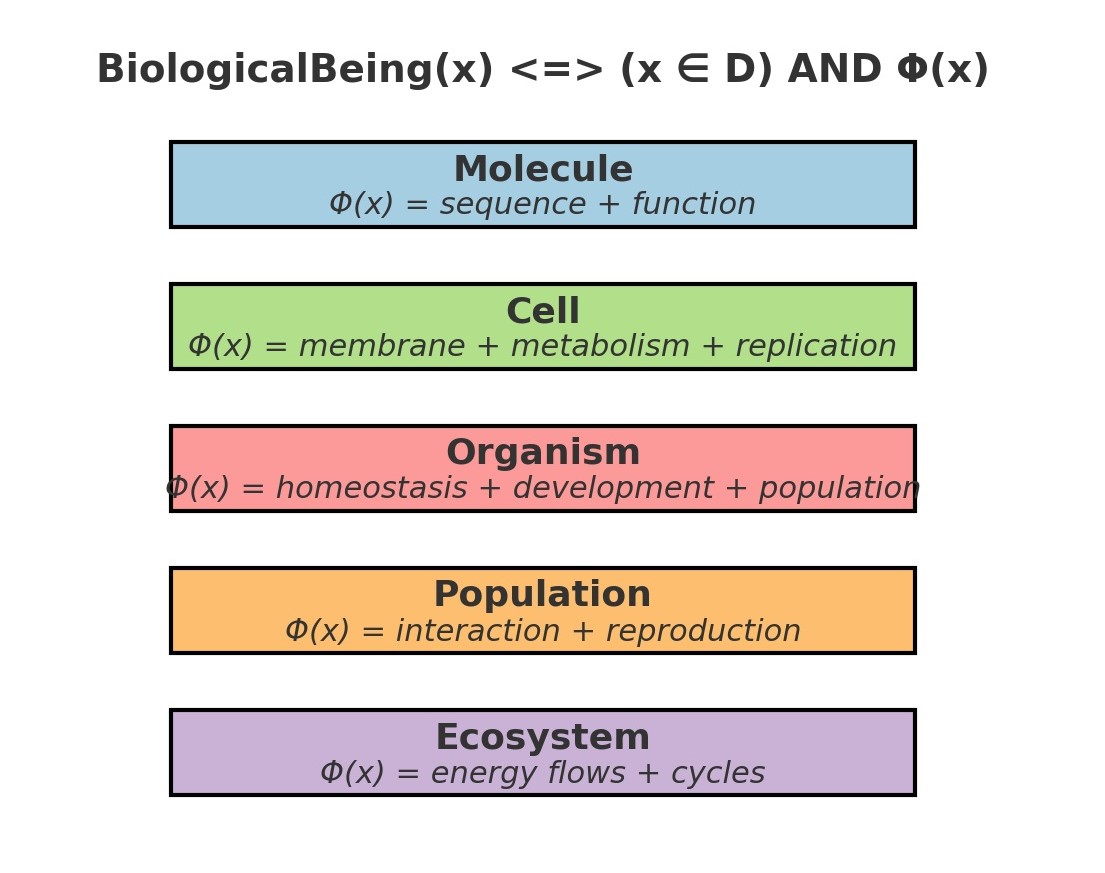

We suggest translating the philosophical notion of being into a mathematical/biological framework. The key step is to treat being not as a metaphysical abstraction, but as existence within a domain. In mathematical logic, existence is expressed by the quantifier ∃, which asserts that “there exists” an object satisfying a predicate. In set theory, being can be interpreted as membership in a well-defined domain. Extending this to biology, we define an entity as biologically real if and only if it belongs to the domain of life and satisfies the minimal conditions of its organizational level. The definition may be expressed as follows:

BiologicalBeing(x)⟺(x∈D)∧Φ(x)

where D is the domain of biological entities and Φ(x) is the predicate that specifies the necessary conditions for existence at a given level. For molecules, Φ(x) may correspond to a valid sequence with biochemical function; for cells, to occurrence of membranes, metabolism and replicative ability; for organisms, to the maintenance of homeostasis and membership in a population; for populations, to reproductive and ecological interaction; and for ecosystems, to flows of energy and cycles of matter. This provides a unified formalism:

∃x∈D:Φ(x)

which encapsulates biological being across scales of organization, from molecules to ecosystems.

Our framework has several advantages compared with other approaches. Unlike purely philosophical ontologies, it is anchored in mathematical precision and testable biological predicates. Unlike reductionist definitions of life privileging one level (e.g., the cell theory or the genetic central dogma), it scales across organizational hierarchies. Unlike purely empirical checklists of life’s properties, it provides a formal language that can be extended, compared and integrated with computational models.

To experimentally test our framework, one must operationalize the predicates Φ(x). For molecules, this means demonstrating that a candidate sequence not only exists chemically, but also performs a biological role, e.g., catalytic activity or regulatory function. For cells, experimental tests may involve assessing whether synthetic minimal cells meet the required predicates of membrane integrity, energy metabolism and reproduction. For organisms, testing involves verifying systemic properties like homeostasis or adaptability. For populations, ecological and genetic methods can assess reproductive interaction. Testable hypotheses include: artificially constructed entities meeting Φ(x) should be regarded as biologically real; modifications to entities removing one element of Φ(x) disprove their biological being; new levels of organization can be formally accommodated by redefining predicates without altering the overall formalism.

The potential applications are manifold. In synthetic biology, our approach could provide a rigorous criterion for determining when a synthetic construct is genuinely living. In astrobiology, it provides a mathematical definition to guide the search for extraterrestrial life by specifying predicates Φ(x) adapted to unknown environments. In systems biology, it enables the formal modeling of biological entities across scales in a consistent language. In philosophy of biology, it provides a way to reconcile metaphysical discourse on being with empirical science. Future research could extend our methodology to evolutionary transitions, such as the origin of multicellularity, by treating each transition as a redefinition Φ(x) at a new level of organization. It could also be applied in computational biology to build formal ontologies that are mathematically grounded rather than descriptive.

In sum, by redefining being as existence within a biological domain formalized through quantifiers and predicates, we create a bridge between philosophy and empirical science. This mathematical ontology might providr a testable language for biological existence, unifying molecules, cells organisms, populations and ecosystems under the same existential principles.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 2025. Nugae -being and life: a mathematical framework for biological existence. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.14486.00328

TRUTH DEPENDS ON THE AVAILABLE INGREDIENTS: A THEORY OF TRUTH GROUNDED IN LINEAR LOGIC

Various theories of truth have been proposed, e.g., correspondence, coherence, pragmatic, deflationary accounts. Yet most of these assume idealized, fully rational agents with unlimited access to relevant beliefs and facts. Many treat truth as a static property of propositions rather than a process constructed or enacted through reasoning processes. These theories tend to overlook the practical constraints faced by real-world knowers such as limited information, cognitive resources and temporal access to data. As a result, many of these theories fall short in capturing the real-time nature of reasoning in decision-making under uncertainty, scientific inquiry and artificial intelligence. What’s needed is a model of truth able to capture how knowledge is built, shaped and constrained in practice.

Linear logic and truth: We propose a resource-sensitive theory of truth based on the principles of the linear logic developed by Jean-Yves Girard that, differently from classical logic, treats information as a resource. A proposition is true for an agent if and only if it can be constructed from available information through a valid sequence of steps. A proposition φ is true for an agent or system if and only if it can be derived from a finite set of informational resources using linear inference:

a ⊗ b ⊗ c ⊢ φ

Here, ⊗ (the tensor operator) signifies that all resources must be present, while ⊢ φ indicates that the proposition φ can be constructively derived. Linear logic is also equipped with the linear implication operator (–o) which governs the transformation from resource configuration to truth claim, preserving the constraints of non-replicability and non-disposability unless explicitly overridden by modal annotations. Therefore, we can express a personal theory of truth in linear logic as: “What I think is true becomes true, but only if I have the right resources (a, b and c) available and I cope with them correctly.”

Overall, our approach points towards a conditional and resource-bound truth rooted in the availability and transformation of informational resources. It’s not enough to just believe something: truth must be constructed from ingredients, much like a proof or a recipe. Truth becomes a dynamic, context-dependent process emerging from what the agent has, knows and can do.

Examples: The following examples illustrate how truth may depend on the presence of specific epistemic resources (e.g., ingredients or inputs) without which a conclusion, however valid, cannot be accessed, confirmed or justified.

- A chef prepares a signature dish and confirms that the ingredients are fresh basil (a), ripe tomatoes (b) and high-quality olive oil (c). Using these, she concludes (φ): the dish will have its characteristic flavor. This belief holds true if all three ingredients are available and used in preparation.

- A team of physicists investigates the existence of the Higgs boson (φ) using theoretical predictions (a), particle collision data (b) and high-precision detector technology (c). Each of these elements is essential: without the theory to guide inquiry, the data to examine or the tools to detect relevant signals, the truth about the Higgs boson cannot be accessed. If all the necessary ingredients and proper epistemic resources are not available, truth is not denied by absence, but made unreachable.

Discussion: By rethinking truth as an operational, context-dependent construct grounded in linear transformations, we situate it within the act of reasoning itself. Our approach thereby aligns with constructivist and proof-theoretic traditions, yet introduces an innovation: reasoning processes are constrained by resource flow. Compared to coherence and correspondence theories, our model tracks how a belief becomes true, not just whether it fits. Compared to deflationary theories, it provides a constructive semantics: truth isn’t just a label; rather it’s something that must be earned through effort. Compared to Bayesian epistemology, it does not require probabilistic access to all alternatives, but instead allows for partial, context-specific reasoning with limited inputs. Still, it may explain Gettier-type problems by identifying when a belief is derived without sufficient or properly used resources.

In our framework, a distinction must be drawn between local truth and global derivability. Local truth refers to what an agent can justify or construct at a given moment, based on the specific resources currently available, like data, concepts, tools or evidence. In contrast, global derivability represents what could be validated under ideal conditions, where all relevant resources are accessible and sharable among agents. This distinction may preserve our dynamic, resource-sensitive approach to truth while allowing for objectivity across contexts.

Our theory could be useful for modeling belief revision, limited rationality, context-sensitive reasoning and inferential constraints in real-world agents. In philosophy of science, it may reframe how theories are justified in terms of finite data sets and experimental evidence. In artificial intelligence, it can support the development of explainable systems justifying conclusions based on consumable data sources. In cognitive science, it may provide a model for bounded rationality and decision-making under informational constraints. In legal reasoning, it can formalize how evidence is used and exhausted in constructing a legal claim. In educational technologies, it can help students learn to construct justified answers based on limited premises. Future research might explore connections between linear truth derivation and epistemic virtue, temporal logic or interactive reasoning in dialogue systems.

Still, our theory generates testable predictions. First, agents trained with resource-sensitive reasoning will outperform classical logic-based agents in environments with limited data access. Second, human subjects will prefer explanations that mirror linear inference patterns, using the available evidence. Third, Gettier-style belief derivations will fail under linear truth derivation models, offering better alignment with intuitive notions of knowledge.

Overall, we suggest that truth is a construct shaped by the correct resources at hand to derive a proposition and the care with which we use them. Like a well-prepared dish or a carefully reasoned argument, truth emerges through action, i.e., through the thoughtful consumption of evidence, context and inference.

Philosophical Addendum: A Heideggerian Integration. A fruitful bridge can be drawn between our resource-sensitive account of truth and Heidegger’s account of language, since both emphasize that disclosure depends on the availability of enabling conditions. Heidegger’s reflections in The Essence of Language deepen our framework by showing that naming is not a secondary act of attaching a label to something already present, but the very event through which a being comes into the open. Without the name, the thing remains hidden, undifferentiated and without presence in a meaningful world. In our resource-sensitive account of truth, this resonates with the claim that truth depends on the availability of specific informational ingredients. Just as for Heidegger the name is the resource that discloses being and allows it to stand within human understanding, in our model data, concepts and tools are the resources that disclose truth and allow propositions to be constructed and validated. Naming, then, may be seen as the primordial epistemic resource: it grants existence within the horizon of meaning, paralleling the way linear logic grants truth within the horizon of reasoning.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 2025. Nugae - truth depends on the available ingredients: a theory of truth grounded in linear logic- DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.12834.34245

MATHEMATICAL TOPOLOGIES OF THOUGHT: A STRUCTURAL METHOD FOR ANALYZING PHILOSOPHICAL FRAMEWORKS

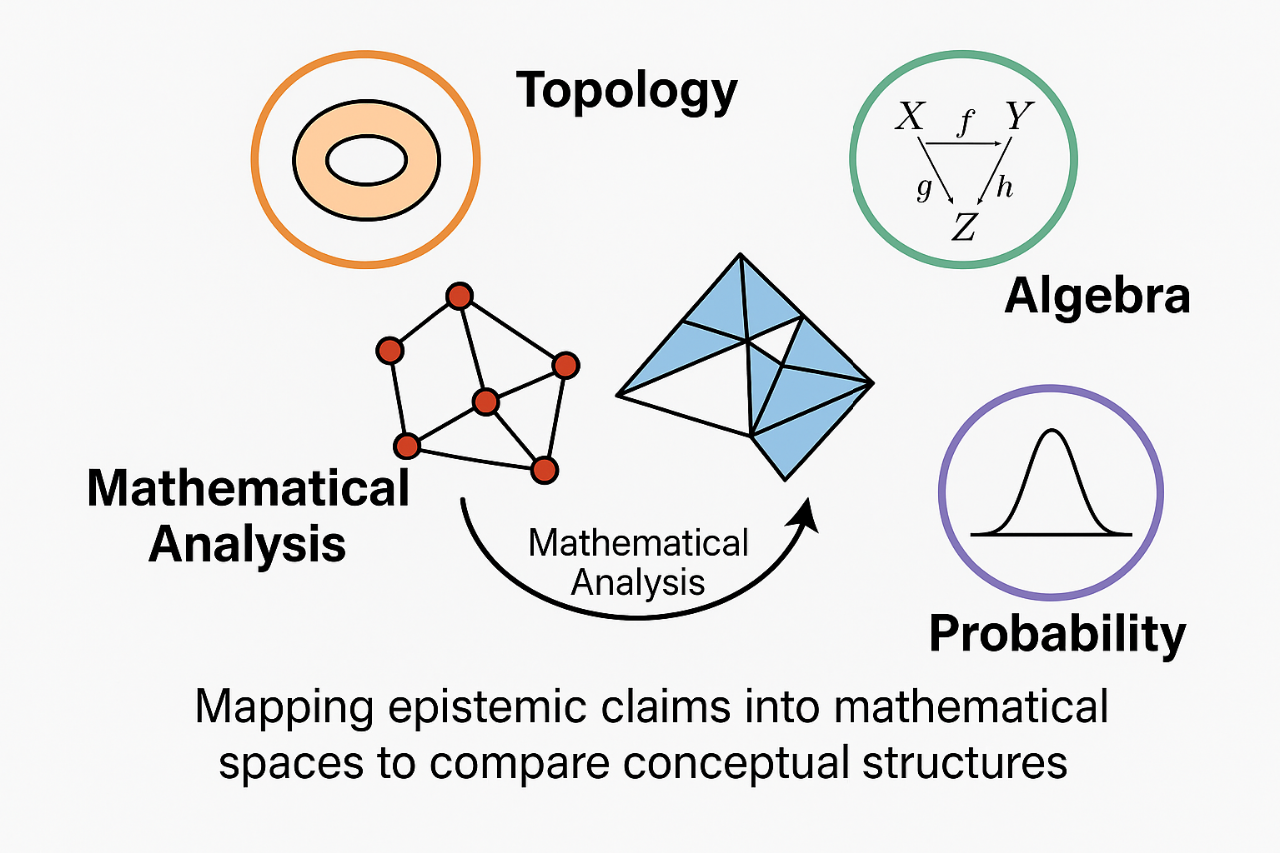

The intersection of mathematics and philosophy has traditionally focused on logic, set theory, and formal semantics. While these tools have proven effective for clarifying arguments and propositions, they often fail to capture the deeper relational and hierarchical structures underlying philosophical systems. Traditional methods like predicate logic, modal analysis, or set-theoretic classification are limited in assessing global structural coherence and dynamic interdependencies in complex conceptual frameworks. To address these limitations, we propose a novel methodological approach that applies topological, algebraic, and probabilistic tools—specifically homotopy theory, sheaf cohomology, and convergence theorems—to the analysis of philosophical arguments. Rather than merely translating arguments into logical syntax, our method maps epistemic claims into mathematical spaces characterized by topological invariants and algebraic structures. This allows us to model conceptual coherence, continuity, and transformation across different systems of thought.

Our method treats philosophical doctrines as embedded structures in higher-dimensional conceptual spaces. Using tools like the Seifert–van Kampen theorem, Kolmogorov’s zero-one law, and the Nash embedding theorem, we may analyze how philosophical positions can be decomposed into substructures, reassembled through formal operations, and compared based on structural similarity or divergence. Homotopy equivalence provides a way to understand how epistemological models can be transformed while preserving essential properties. Meanwhile, probability theory enables a measure of epistemic stability or variability within those models.

This structural formalization provides several potential advantages. It allows for more rigorous comparison between philosophical frameworks, enables the visualization of conceptual dependencies, and provides metrics for evaluating internal consistency and coherence. The methodology opens the door to applications in artificial intelligence, where philosophical concepts could be operationalized within machine learning systems or automated reasoning engines. It also holds promise for digital humanities and the computational analysis of historical texts. Our approach is distinct from existing techniques in its ability to preserve both local and global properties of philosophical structures, offering a new level of precision and formal clarity. Unlike purely logical or interpretive analyses, it introduces measurable, testable models of philosophical thought, setting the stage for future empirical investigations. Testable hypotheses include whether philosophical systems exhibiting homotopy equivalence correspond to similar cognitive models or whether certain topological features predict conceptual evolution.

Overall, this method represents a conceptual innovation to bridge mathematical formalism and philosophical analysis, providing a framework for future interdisciplinary research in epistemology, metaphysics, AI, and beyond.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 2025. Topological and Algebraic Patterns in Philosophical Analysis: Case Studies from Ockham’s Quodlibetal Quaestiones and Avenarius’ Kritik der Reinen Erfahrung. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202502.1518.v1.