Medicine

Arturo Tozzi

Former Center for Nonlinear Science, Department of Physics, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas, USA

Former Computationally Intelligent Systems and Signals, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

ASL Napoli 1 Centro, Distretto 27, Naples, Italy

For years, I have published across diverse academic journals and disciplines, including mathematics, physics, biology, neuroscience, medicine, philosophy, literature. Now, having no further need to expand my scientific output or advance my academic standing, I have chosen to shift my approach. Instead of writing full-length articles for peer review, I now focus on recording and sharing original ideas, i.e., conceptual insights and hypotheses that I hope might inspire experimental work by researchers more capable than myself. I refer to these short pieces as nugae, a Latin word meaning “trifles”, “nuts” or “playful thoughts”. I invite you to use these ideas as you wish, in any way you find helpful. I ask only that you kindly cite my writings, which are accompanied by a DOI for proper referencing.

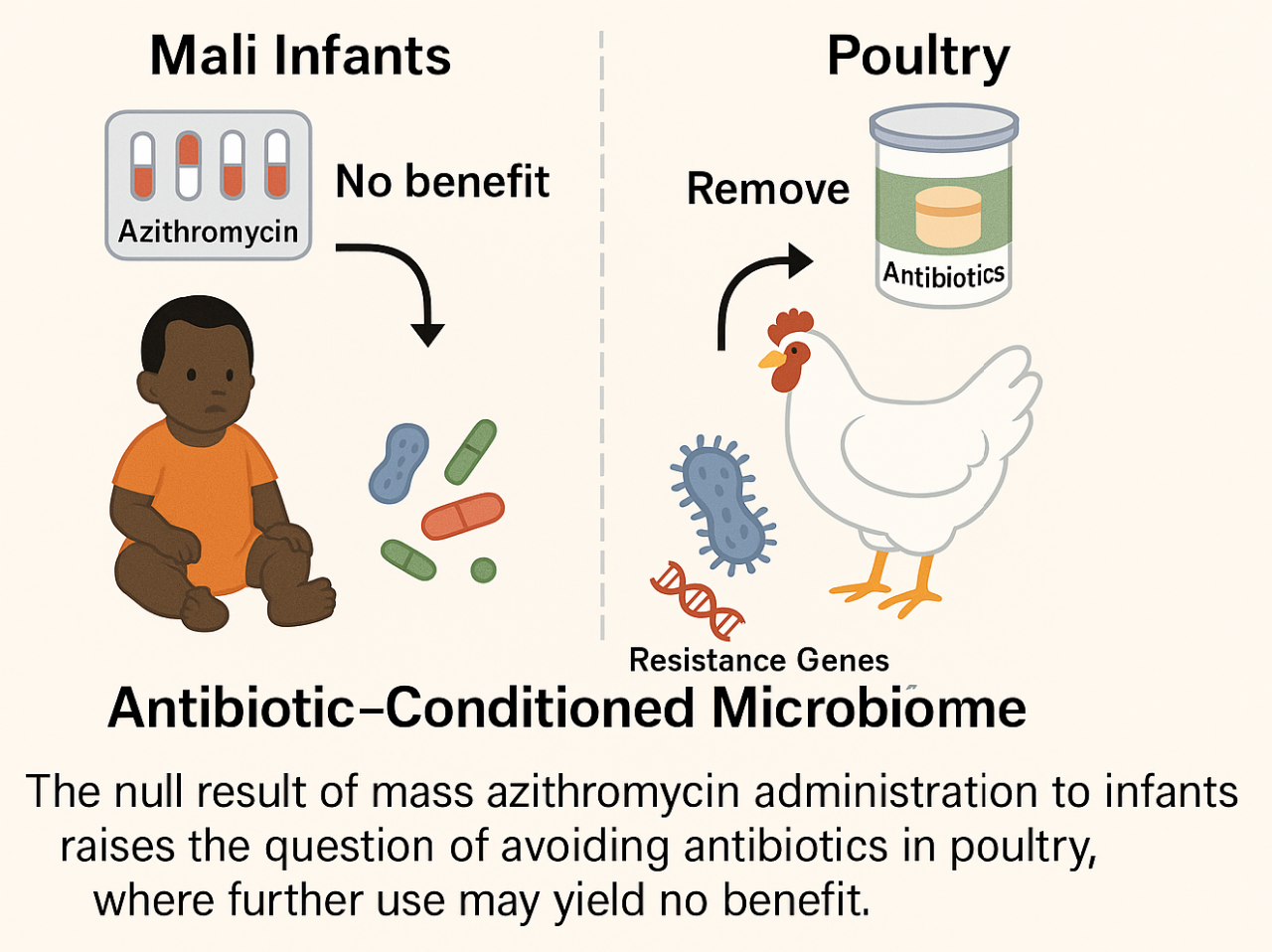

NUGAE - WHEN ANTIBIOTICS STOP WORKING: TOWARD DRUG-FREE POULTRY SYSTEMS?

A large multicenter trial recently published in NEJM (2025) examined whether mass administration of azithromycin to infants in Mali could reduce mortality or infectious disease incidence. The result was negative: no significant differences were found between azithromycin and placebo groups. This finding could challenge a long-held assumption in both medicine and agriculture, i.e., that broad, preventive antibiotic exposure is intrinsically beneficial. For decades, the success of antibiotics in treating acute infections justified their prophylactic use in large populations, including livestock. The NEJM null result would, paradoxically, serve as a model of health without intervention, a warning that the time has come to abandon prophylactic antibiotics altogether.

Experimental validation could involve controlled poultry studies where macrolide use is completely suspended, monitoring infection rates, productivity, and microbiome structure over several generations. If outcomes remain stable or improve, this would confirm that antibiotic withdrawal restores resilience rather than inviting disease. Predictably, one should observe transient microbiome fluctuations followed by a re-emergence of balanced commensal populations and decreased antibiotic-resistance gene prevalence.

An antibiotic-free approach to poultry, if validated, has clear advantages over existing approaches focused on developing new antimicrobial compounds or rotating drug classes. Instead of escalating the biochemical arms race, it reframes antibiotic policy as an ecological optimization problem. The benefit lies not in invention but in withdrawal, letting microbial communities regain their adaptive coherence while reducing resistance pressure across ecosystems.

Beyond poultry, this shift heralds a broader transformation in health management. It invites a future where biological stability replaces chemical control, where we learn to cooperate with microbial ecosystems rather than suppress them. The implications reach from agriculture to neonatal medicine, from antibiotic stewardship to microbiome engineering. The failure of azithromycin to confer additional benefit may not mark the end of antibiotics, but the beginning of a world mature enough to live without them.

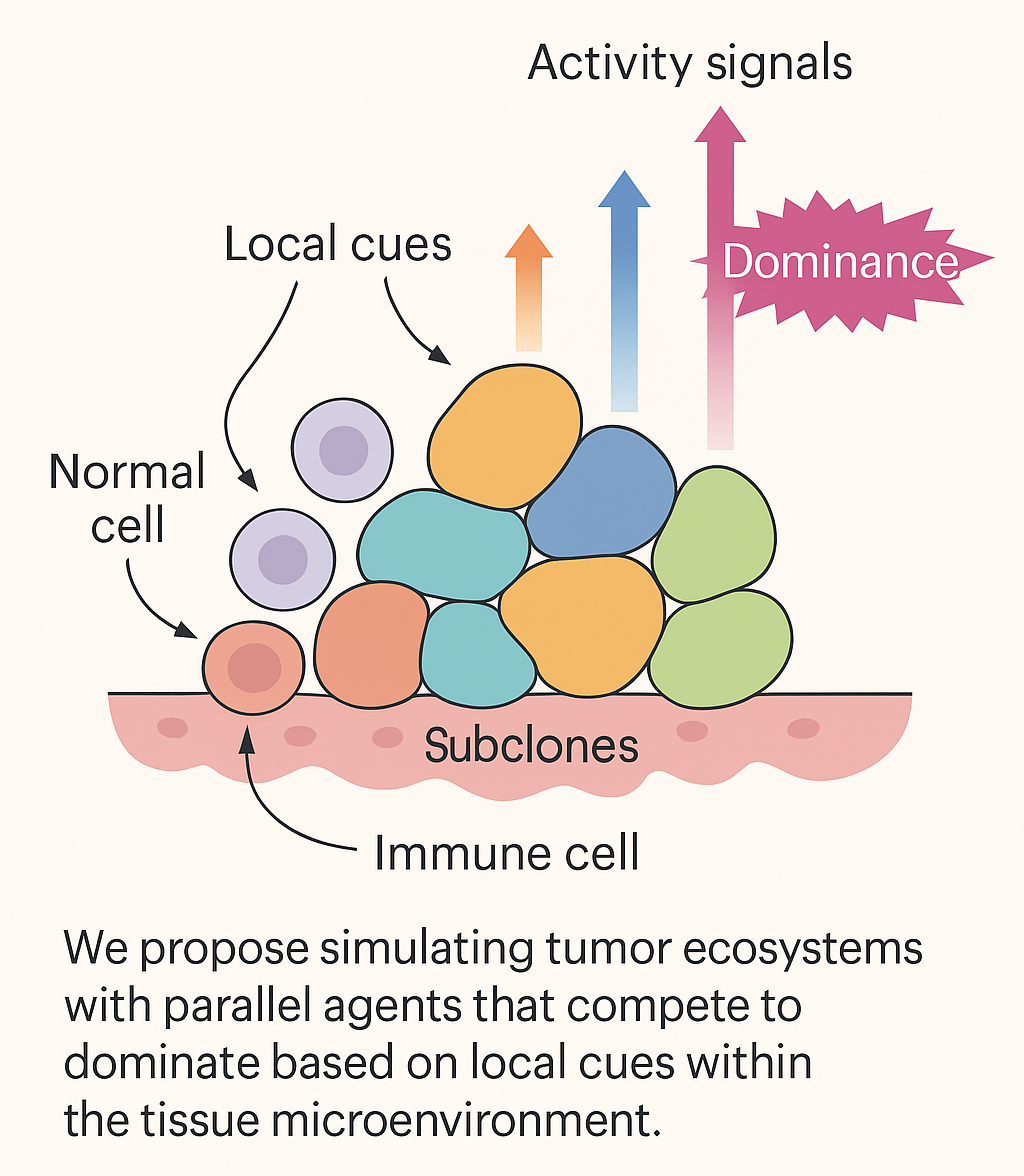

NUGAE - PANDEMONIUM WARFARE: MODELING TUMORS AS BATTLING CELLULAR ARMIES

Current tumor modeling approaches either treat tumors as homogeneous masses or focus solely on their genetic features. These reductionist frameworks fall short in explaining how tumors behave over time, particularly in the face of selective pressures like immune surveillance or therapy. They ignore the spatial and temporal complexity of the tumor microenvironment, i.e., the arena where different cellular factions interact, compete and adapt. As a result, we lack the tools to understand and predict why some potentially dangerous cells are eliminated while others escape detection and proliferate. As recent studies have shown, cancer is not simply characterized by uncontrolled cell growth, rather is the outcome of ongoing competition between different cell populations within the body. Far from being passive victims of malignant transformation, healthy cells can detect and actively eliminate their dysfunctional neighbors through cell competition. Such quality-control mechanism, long studied in developmental biology, involves healthy cells identifying and outcompeting cells that are genetically or metabolically abnormal. Internal cellular conflicts play a significant role in maintaining tissue integrity and eliminating potentially precancerous cells before they establish dominance. Cells can push out, kill, or even cannibalize their defective counterparts, creating a hidden battlefield that influences also the early stages of cancer development.

Given these premises, we propose a conceptual and computational framework inspired by Selfridge’s Pandemonium architecture. Originally designed to assess how perception emerges from competition among autonomous “demons,” in our adaptation each “demon” is not a feature detector, but a biological agent, such as tumor subclones, immune cells, stromal components, signaling pathways. These agents act independently, sensing their local environment and “shouting” based on their internal activation levels. Their competition determines which cell types or behaviors become dominant within the tumor at a given time.

This idea could be implemented by employing agent-based modeling, a simulation technique well-suited to systems composed of interacting individuals with variable behaviors. Each agent (or demon) may be defined by specific traits: proliferation rate, resistance to stress, responsiveness to immune signals or metabolic needs. Still, each agent may detect environmental cues (e.g., nutrient availability, drug concentration, oxygen levels) and adjusts its activity accordingly. Then, agents may compete for dominance within discrete microenvironments. The “loudest” agents, i.e., those most strongly activated, shape the local behavior of the tumor, determining whether it grows, regresses or mutates.

Unlike top-down or equation-based models, our decentralized architecture permits emergent behavior. Cells don’t follow a predetermined script. Instead, their behavior arises from their local interactions and environmental context, mirroring the chaotic but structured nature of real tumor progression. Moreover, the modular nature of our model allows for expansion: new agents can be added to simulate specific immune cells, therapies or even evolving tumor phenotypes without rewriting the entire system. The advantages of our approach are manifold. First, it captures both intra- and inter-clonal competition, reflecting the ecological dynamics within the tumor microenvironment. Second, it allows for realistic complexity, showing how multiple forces (e.g., hypoxia, drug pressure, immune infiltration) interact to shape tumor evolution. Third, it has predictive power: the model can simulate how interventions like drug treatment or immunotherapy might shift the competitive balance within the tumor, potentially forecasting resistance or relapse. Finally, our approach is mechanistically informative: by tuning parameters or altering environmental conditions, researchers can explore why some interventions fail and identify leverage points where the competitive landscape could be tilted in favor of healthy or therapeutic agents.

Our model also generates testable experimental hypotheses. For example, would enhancing the “voice” of normal epithelial cells in early lesions reduce tumor incidence? Could environmental modulation like increasing oxygen or decreasing glucose change the outcome of clonal competition? Might the introduction of low-dose therapies at early stages shift dominance away from aggressive clones without selecting for resistance? Our architecture could be extended by incorporating real-world data (e.g., single-cell transcriptomics or patient-specific mutation profiles) to customize simulations and guide personalized therapy planning. It could also be applied to model tumor–immune dynamics by adding immune “demons” that sense abnormal cell activity and compete to neutralize it. Similarly, the model could be adapted to assess metastasis by simulating competition between local tumor cells and metastatic seeding cells entering new environments.

Overall, by drawing from cognitive science to model cellular competition, we propose a new way to conceptualize tumors, not as uniform masses, but as battlefields of competing cellular factions. Our Pandemonium-inspired framework may provide a richer understanding of tumor ecology and open the door to more adaptive, strategic interventions in cancer treatment.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. 2025. Nugae -Pandemonium Warfare: Modeling Tumors As Battling Cellular Armies. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.35698.21444

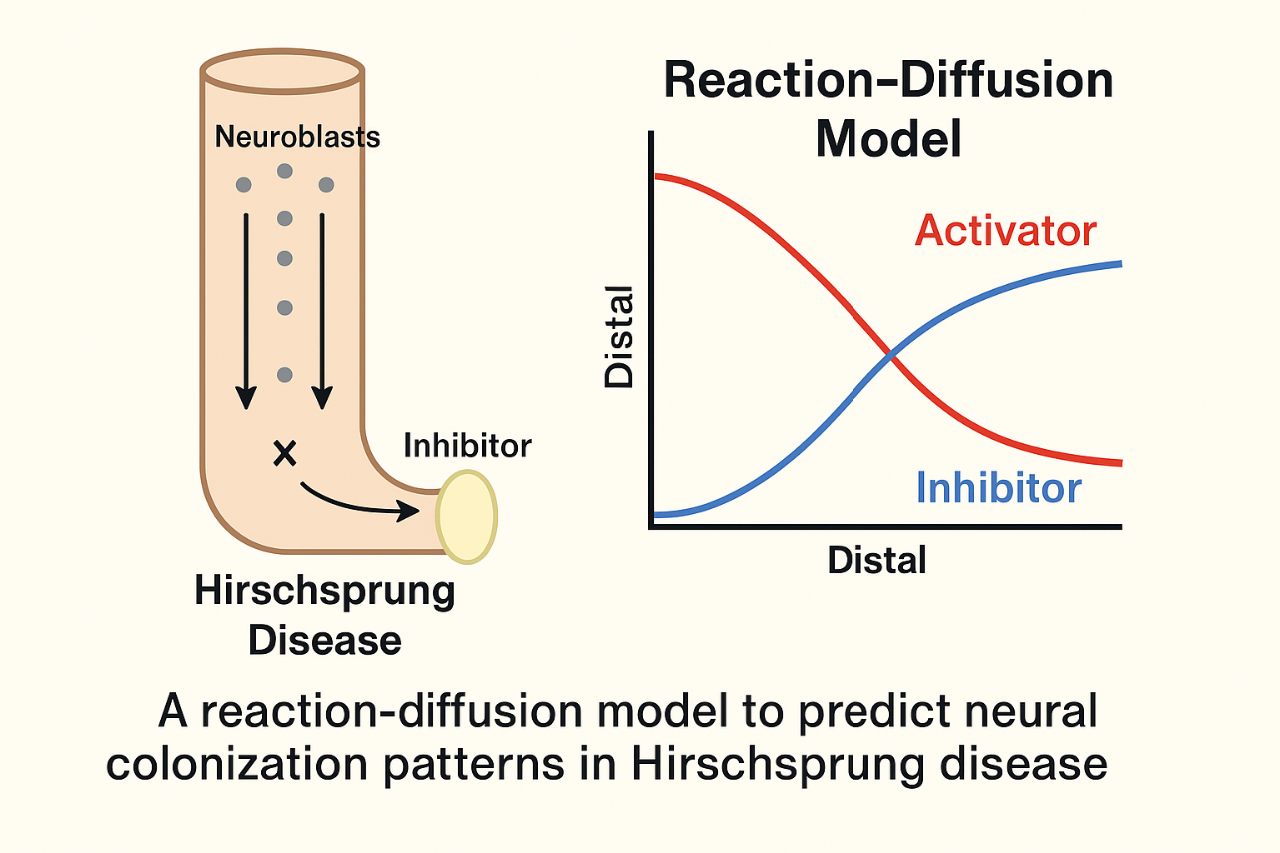

A REACTION-DIFFUSION MODEL FOR PREDICTING NEURAL COLONIZATION PATTERNS IN HIRSCHSPRUNG DISEASE

Hirschsprung disease (HD) is a congenital disorder characterized by the absence of neurons in the distal bowel, leading to severe digestive dysfunction. Current surgical treatment requires removal of the affected gut segment. However, the extent of the aganglionic and hypoganglionic regions varies greatly between individuals, making it difficult for surgeons to determine how much intestine to excise to restore function effectively. Traditional models of HD attribute the disease to a failure of neuroblasts, originating from the neural crest, to complete their migration along the rostro-caudal (head-to-tail) axis during embryonic development. While this explains the basic defect, it does not offer a quantitative or predictive framework for estimating the extent of neural deficiency. Current techniques rely on histological sampling during surgery, which may be imprecise and time-consuming.

To address this limitation, a novel approach is proposed based on Turing’s reaction-diffusion (RD) model—originally devised to explain biological patterns such as animal skin markings. In this framework, gut colonization by neural precursors is modeled as a diffusion process governed by two competing factors: an “activator” (representing neuroblast density) and an “inhibitor” (a local factor that prevents colonization, stronger in the distal gut). The interaction between these elements, described by a system of partial differential equations, results in predictable patterns of neural distribution.

By modeling the intestine as a cylinder colonized from the proximal end, the RD framework simulates how an imbalance between activator and inhibitor can produce decreasing neural density toward the distal colon. This matches the pattern seen in HD and offers a theoretical tool for anticipating the location and extent of impaired tissue. This method stands apart from existing techniques by introducing a quantifiable, biologically grounded model that could guide surgical planning. Unlike genetic or histological methods, which can be complex or delayed, the RD model allows for computational simulation based on general parameters of gut development and neuroblast behavior.

The potential applications of this model extend beyond surgical planning for HD. It may provide insights into other neurodevelopmental disorders involving impaired cellular migration or differentiation. Future research could refine the model to account for variable gene expression, tissue growth dynamics, or interactions with the gut microenvironment. Experimentally, this approach opens testable hypotheses: for instance, whether specific local inhibitory signals can be identified biochemically, or if manipulating these factors in animal models alters neural colonization patterns in line with RD predictions. This could pave the way for both diagnostic and therapeutic advances.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi, A. To Know them, Remove their Information: An Outer Methodological Approach to Biophysics and Humanities. Philosophia (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-022-00576-y.

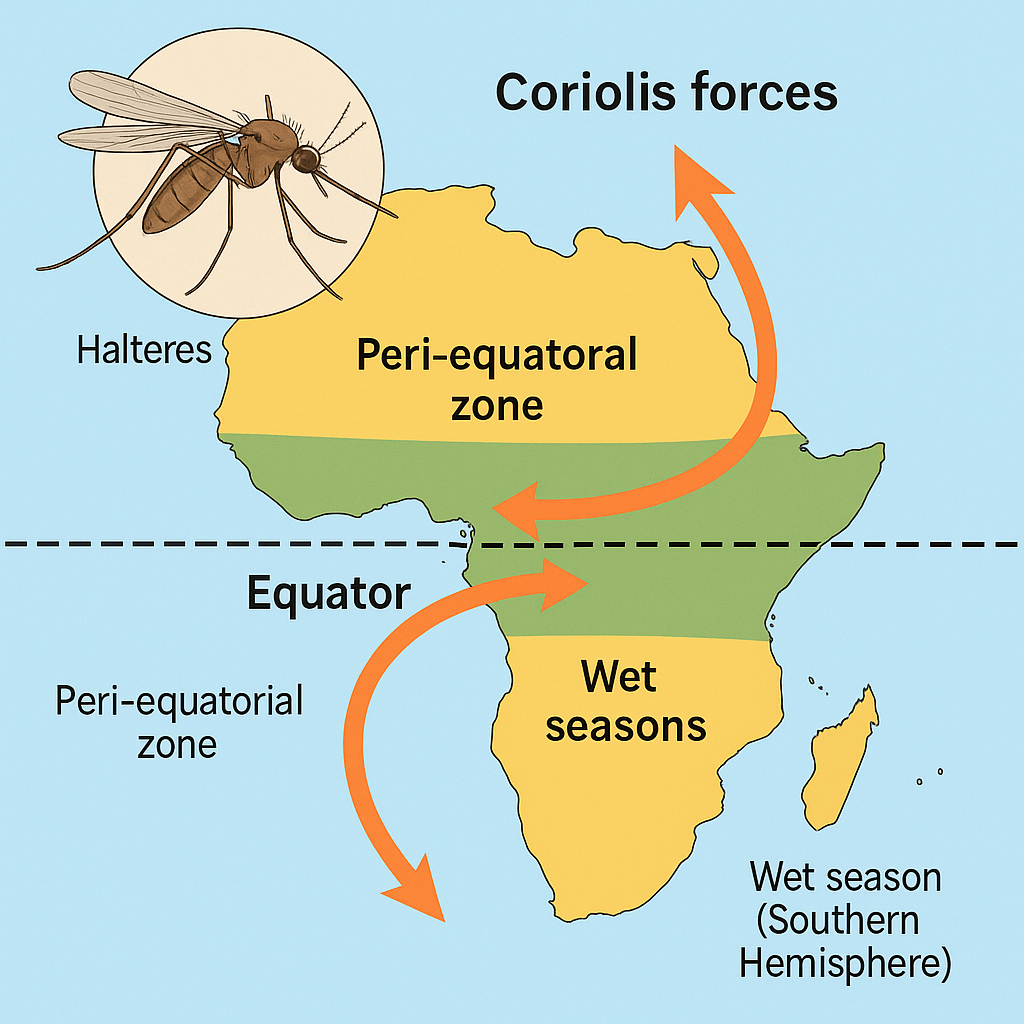

HARNESSING CORIOLIS-SENSITIVE MIGRATION IN MOSQUITOES TO IMPROVE MALARIA PREVENTION TIMING

Current malaria control strategies focus on localized vector suppression, but face major limitations: they often fail to address the long-range seasonal migration of Anopheles mosquitoes. Traditional assumptions held that mosquitoes travel only short distances. However, new findings show that gravid females can migrate hundreds of kilometers at high altitudes, riding wind currents between regions of seasonal rainfall. These migration patterns help explain how mosquito populations suddenly surge at the onset of wet seasons in areas that previously had none during the dry season.

One major limitation in current prevention approaches is the failure to account for these long-distance migrations, which can repopulate regions even after successful local vector elimination. Moreover, these migrations may help spread insecticide-resistant mosquito populations or drug-resistant parasites across vast areas, undermining regional efforts at disease control.

To address this, we propose a novel hypothesis: that mosquitoes may use their halteres (flight-stabilizing sensory organs) to detect Coriolis forces near the equator and navigate across hemispheres in search of wet breeding grounds. This concept leverages the topologically robust nature of equatorial airflows — such as Kelvin and Yanai waves — which arise from Earth’s rotation and break time-reversal symmetry, potentially providing stable migratory corridors. Unlike random windborne dispersal, this model suggests a biologically tuned, directionally sensitive mechanism driving equatorial mosquito migration. This hypothesis opens new avenues for malaria prevention. For instance, if mosquitoes consistently migrate across the equator before regional wet seasons, timing the administration of short-lived interventions — such as monoclonal antibodies — just before these migrations could significantly disrupt transmission. Specifically, applying these strategies during February–March in the Northern Hemisphere and September–October in the Southern Hemisphere could align with anticipated mosquito influxes.

Compared to conventional vector control, this method targets predictable large-scale movements rather than reacting to local outbreaks. It aligns with emerging findings in atmospheric science, entomology, and disease modeling. Potential applications include integrating this understanding into climate-driven forecasting models, gene-drive strategies, or aerial surveillance systems. Future research should investigate whether mosquitoes actively detect Coriolis-induced cues via their halteres, possibly through lab-based behavioral experiments or field tracking with scented markers or genetic tagging. A key hypothesis to test is whether migration patterns correlate with equatorial Coriolis dynamics and whether disrupting this navigational cue impairs long-range flight. Confirming such mechanisms could revolutionize our understanding of vector ecology and optimize seasonal malaria control efforts across hemispheres.

QUOTE AS: Tozzi A. Anopheles' peri-equatorial migration via Coriolis forces (electronic response to: Wu RL, Idris AH, Berkowitz NM, Happe M, Gaudinski MR, et al. 2022. Low-Dose Subcutaneous or Intravenous Monoclonal Antibody to Prevent Malaria. N Engl J Med 2022; 387:397-407. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203067). How do mosquitoes survive during the dry African seasons?